Last night a friend rang with a mathematics problem. He is selling a property with an irregular shape and wanted me to check his calculation of the area. Just in case you want to try before I proceed, the boundaries are straight with lengths (in order going around) 36.0, 21.3, 28.1 and 22.7 metres.

When I told him the problem was impossible and I could not answer, he replied that I had been studying maths for 70 years and still could not solve a simple problem. There must be a major problem with the education system, he said. I tried to explain by showing him a square with all sides 10 m and them squeezing it into a skinny rhombus. But by this time he was off on his criticism of the world and the elites that run it.

In mathematics we are rightly proud of proofs where problems that seem solvable are shown to be impossible. But in school mathematics the student never meets such problems. Perhaps a sprinkling of impossible problems might narrow the gap between the average citizen and the so-called elites.

So I’m seeking suitable problems to be included, without warning, in textbooks. Here is one, Year 11 level, where the first part suggests the second is do-able.

1a) A triangle has sides of length 10, 12 and 14 m. Find the area enclosed.

b) A quadrilateral has sides with lengths (in order going around) 36.0, 21.3, 28.1 and 22.7 metres. Find the area enclosed.

This could lead into a discussion of congruence, or perhaps why builders make triangles in addition to rectangles, or how surveyors record properties. Or given the sides of a quadrilateral what extra information is need to find its area? Are the edge lengths of a tetrahedron sufficient to determine its volume?

In the previous question there were too many objects that fitted the description. There are also questions where the object described does not exist. Worth a run?

- A triangle has sides 19 cm, 8 cm and 9 cm. Find the area enclosed.

More problems please?

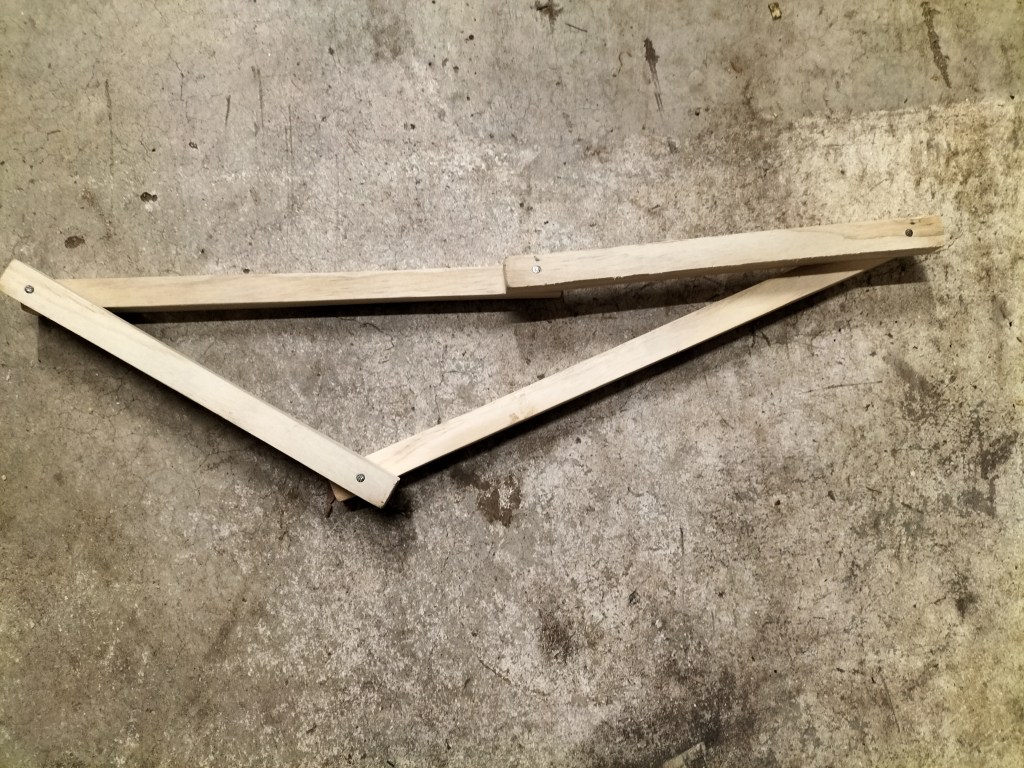

PS: On the basis that practical minded people learn best from physical models, I made one such to solve the initial problem. Here are some pictures.

Just remembered a computation that I used as an introduction to beam theory when teaching engineering students. It’s understandable at a secondary level by students who know some statics.

Leave a comment