Part of the fun of one-on-one tutoring is the chance to tailor a lesson to the interests of the student. Suppose we have a student, let’s call her Idil, who’s first passion is writing and language, and who seems curious about the world and its history. She was initially bored by mathematics but responded to an accelerated course. Having devoured the primary school

syllabus and more, it was time for negative numbers. So how should I guide this?

When in teaching mode I treat mathematics as a language. This is more digestible for students and also gives me the opportunity to stray into the universe of applications. With negative numbers that means accounting. Negative number have been discovered/invented at least twice: in China and India. In each case they arose in relation to matters of trade; assets and revenue are positive while liabilities and expenditure are negative. I guess most teachers still present negatives in this context; for example, removing a debt is equivalent to adding a credit. But I wanted to go the full monty, to teach the mechanics of the balance sheet.

Why? Well I have long held this theory that the adoption of negative numbers by Europeans was due to that of double entry accounting. European mathematicians had long been using the Indian notation for numbers but mostly baulked at the idea that numbers could be negative. But in 1494, Pacioli published the double entry system in a work that

also allowed numbers to be negative. Mathematicians continued to reject negative numbers for a while, but in my theory they were swamped by the new army of accountants.

I had another motive in discussing balance sheets. When I was at school, a number such as −3 was termed “minus three”. It was in the 70s that I noticed that teachers were calling this “negative three” and keeping the word “minus” for subtraction. Ever since I have been wondering why the symbol − is used for two different things. It is annoying. For example, when subtracting a negative, we are inclined to use parentheses to separate the two instances of the symbol; 2 − (−3) = 2 + 3. Perhaps the conflation might have occurred in accounting.

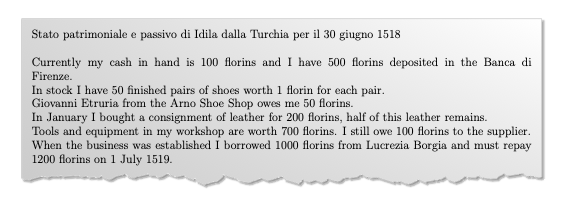

Regardless of these issues I think the lesson that eventuated is a worthy addition to the teacher’s arsenal, perhaps slightly modified for classroom use. So here it is. We begin with a statement from Idil’s ancestor in Florence who is a shoe manufacturer.

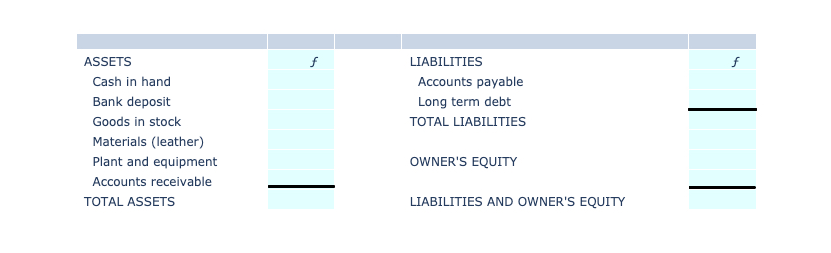

We need to classify the items discussed as either assets or liabilities. Below I show an empty balance sheet wherein the student can enter these.

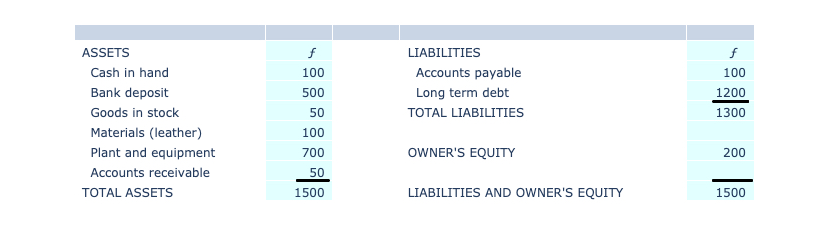

In my experience, students enjoy the task of deciding where items should go, though they may need some guidance here. Once the assets and liabilities are inserted and added we need to explain that the two columns must balance, so the equity is added to achieve this. Below we see that the business has a value of 200 florins that is added to the total liabilities.

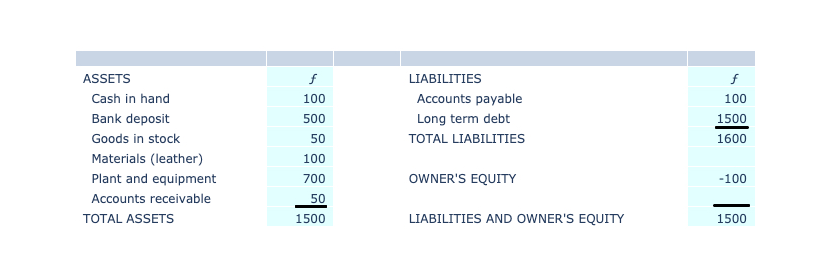

Now some bad news. Idila’s loan is increased by 300 florins; Lucrezia Borgia has decided to retrospectively increase the interest on that loan. Can she do this? People who inconvenience the Borgia family have been found floating in the Arno river. So we need to recalculate.

This time the liabilities total is greater than total assets. So 100 florins must be subtracted to make the balance. Idila owes more than she owns. Her equity is now less than zero. We call this a negative number. Here ends the first lesson.

Notes

The reader may have noted that in order to show that the equity is subtracted, then a minus sign appears before the equity. I was guessing that this is how a sign originally meant for subtraction became associated with the negative number. But Wikipedia suggests that the earliest use of the minus was for a deficit, (Widmann 1489) so perhaps the association occurred in the reverse direction.

This is purely an introductory lesson to show the student that negative numbers can have a genuine application. The topic will require several hours of practice with the mechanics of calculating with negatives.

If the student would prefer a happy ending then you may report that Lucrezia Borgia died before the loan repayment was due, leaving no record of the loan. Idila was suddenly rich and returned to Turkiye with a great collection of shoes.

I would love to know how readers have taught the topic, or intend to. Please feel welcome to comment below.

Leave a reply to JJ Cancel reply