In the site Bad Mathematics, Marty and Christian R have recently been discussing the relation between History and Mathematics. Their discussion was wide ranging but the pointy end of it seems to be whether maths teaching benefits from presenting a topic in its historical context. Such an approach may offer a natural introduction, motivating the topic and leading directly to applications. The alternative is to offer the modern pared-down version, direct and logical. At the same time I was preparing this post which relates my personal experience of a lecture that offers evidence for both sides. The topic was Lagrange multipliers, so let me start with a quick introduction for newbies.

Suppose we wish to find the minimum value for the function but are restricting the search to where

, “constrained optimization”. One method that used to be taught in schools is to solve the constraint for one of the variables, say

, and then substitute this into the function, giving

. It’s now a function of a single variable so let’s use calculus to find the turning point. [Overkill here as the function is a quadratic.]

so

giving a minimum of

.

The Lagrange method instead considers a combination of the objective and the constraint, . Here, instead of reducing the variables to just one, we have increased them to three by adding this mysterious variable

, called the Lagrange multiplier. Now we compute the partial derivatives

,

and

, equate them to

, giving 3 equations for 3 unknowns:

,

and

. These show again that

,

, and for what it is worth,

.

Why make things harder in this way? Well in many cases the constraint equation cannot be solved to get one variable in terms of the other. For example, what if the constraint is ? The Lagrange multiplier method will still work, at least it will give a system of 3 simultaneous equations that can be solved numerically.

So how did my lecturer approach this? She started by defining “infinitesimals”. Yes! Back in the 60s, optimization research papers and textbooks were still using those critters that are infinitely small but not zero. But she must have realized they were problematic because she had a new definition. Instead of defining to be infinitely small, it was just an ordinary non-zero number. Then for

she defined

to be

. Then

really is the fraction

. To obtain a maximum for

she just put

. Looking back now I see that she was effectively putting

so maybe she was ahead of her time!

My lecturer then introduced the problem of optimizing with constraint

. Magically the new function

appeared and she proceeded to prove that it gave the same constrained optimum if we somehow put

. But my brain refused to follow the reasoning; I was still staring at that damned

. Where had it come from? The lecture might have been logically correct, but for me not psychologically correct.

Over the next few decades I would occasionally recall these Lagrange things, but never found the time to solve the mystery of their origin. Until 1999 that is, when I accepted a job in a research team at Monash, implementing optimization algorithms in a suite of software. Before starting I decided to resolve the mystery, just for self respect.

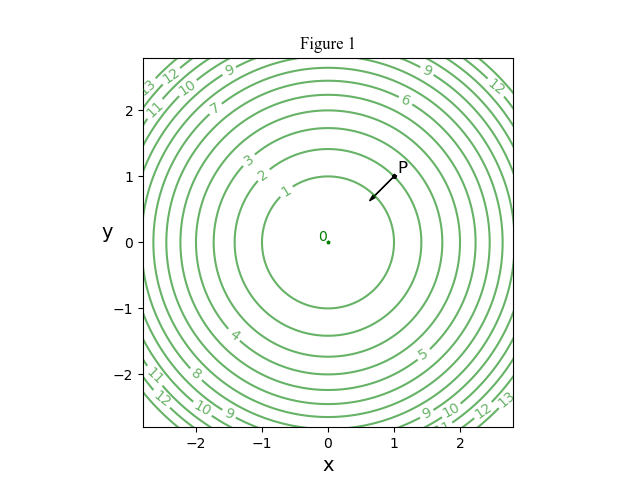

Lagrange and I shared the same handicap. We both learned calculus as a tool for modelling dynamics. We both missed out on the modern approach that divorces subjects from their roots. In Lagrange’s day the hot topic was the use of potential theory for dynamics. For example if a particle is moving under a scalar potential , the force acting on it is the vector

. In Figure 1 we see level curves for

. At the point

the force will be

(shown not to scale) which will push the particle toward the origin. At the origin the force is zero, so the particle is in equilibrium there. The origin gives stable equilibrium which here corresponds to a minimum potential for

.

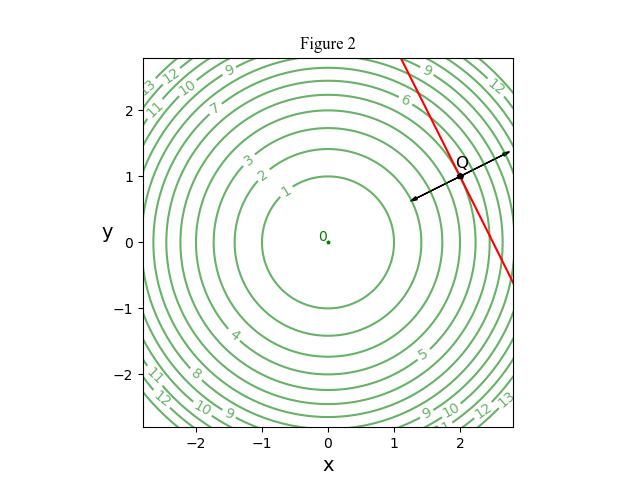

Now let’s introduce the constraint . If the particle is constrained to that line then the new minimum potential is at the point

in Figure 2. How does that happen? To keep the particle on the line there must be a reaction force holding it there. But the particle is free to move along the line, so this force must be perpendicular to that line. Thus it will have the form

. But there is still the force

due to the potential field. For minimum

there is equilibrium; the two forces must exactly balance,

. Writing

the minimizing point must satisfy

and

. That mysterious

is just a scale factor to give the correct reaction force.

Time for a literature search. Damn. Wikipedia gives almost an identical derivation to mine. So I pull down my 70s texts on optimization. None use this approach. One takes the lecturer’s route of plucking the Lagrange multiplier from nowhere. The others find different algebraic routes, none obvious. My conclusion is that Lagrange almost certainly used the dynamics argument but this was neglected when calculus was cleansed of physics.

How does this answer the issue of the historical approach to teaching mathematics?

- Treating optimization as an exercise in Physics makes the derivation intuitive and easy. The historical approach is good.

- Sticking to the traditional use of infinitesimals just muddies the issue for a modern reader. The historical approach is bad.

Furthermore

for those interested in the optimization theory …

A: What would it mean if we found ?

B: We have been finding stationary points. Usually the nature of the optimization problem fingers the point as giving either a minimum or a maximum. If in doubt then one may resort to the Hessian matrix.

C: Suppose that we optimize with several constraints

. Then for equilibrium, the force due to the potential function

must be balanced by a linear combination of reactions from the various constraints,

. This gives

equal to

and all its derivatives zero. Here the force due to the potential is in the space spanned by the

; a natural introduction to the more abstract linear algebra.

D: If a constraint is an inequality constraint, rather than an equality one, then if that constraint is active, the corresponding force vector has a specified sense. The Lagrange multiplier for that constraint will be either strictly positive or strictly negative, depending on the allowed direction of the inequality. We are on the road to Kurush-Kuhn-Tucker theory.

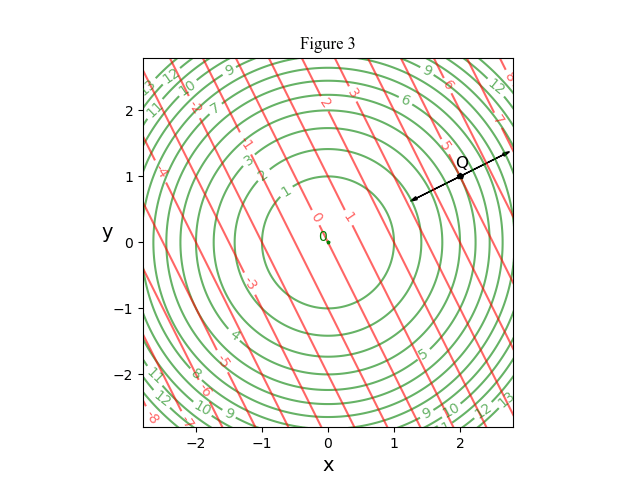

E: Returning to 2 dimensions and 1 constraint, an engineer may be interested in the trade-off between the constraint and the minimum . What is the “sensitivity” of the minimum to variations in that constraint? Figure 3 shows (in red) points allowed by the constraint

for various

. As

increases from

, the corresponding optimal point moves outward from

and the minimal

will increase. Keep in mind that

gives the direction of maximal rate of change of

and its magnitude is that rate of change. So if

is displacement outward in the force direction, then

. Similarly

. Hence

, giving

. At the point

we saw that

, so

. So

measures the rate of trade-off between the constraint parameter

and the optimal

.

F: Looking again at Figure 3, suppose that we swap the roles of the families of contours. Now the green contours are the constraints and the red ones represent the function to be optimized. This time we obtain . For constraint

the optimal point is again

giving

although this time we have maximized

.

will be

. This new problem is called the “dual” of the original.

G: Here is a classic pair of dual optimization problems. A nice exercise is to draw the relevant level curves.

A farmer is fencing a rectangular paddock on 3 sides. (The other side uses an existing fence.)

- Suppose the new fence has length 800 m. Find the dimensions of the paddock that has maximum area.

- Suppose instead that the enclosed area needs to be 80,000 m2. Find the dimensions of the paddock that will use minimum fence length.

H: The physical interpretation of Figure 3 is a gift that keeps giving. In that figure interpret the two contour families as competing objectives. This leads to a new direct search algorithm for bi-objective optimization.

Leave a reply to Dr Mike Cancel reply