The normal distribution is a fixture in any first course on statistics. My experience teaching the topic is almost entirely in courses servicing students whose main interest is elsewhere: management, accounting, science or psychology. My approach is I guess typical; I present the distribution as a picture like the one below. I claim that this is a useful model for a continuous random variables and explain how probabilities are given by areas under the curve.

Here the constant is the mean of this distribution and

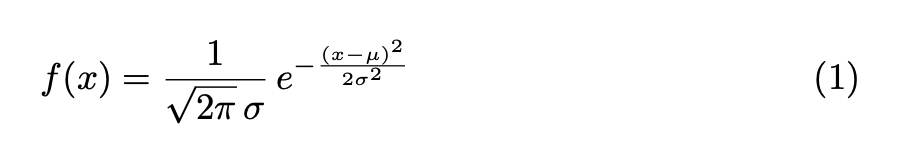

the standard deviation. I don’t give any theoretical underpinning; I don’t even give the formula for this curve. In case you have never seen that formula it is the “Gaussian function”

Frightening hey? even the words “probability density function” may scare the horses. I do however teach that the standard deviation is the horizontal distance between the mean and the points of inflection either side which seems to give some feeling for the curve.

Some useful properties of the normal distribution are common sense. For example, if has a normal distribution, then for

the distribution is moved to the right by 10 units, and for

the distribution is spread out by a factor 2. But recently, tutoring a very good secondary school student, she thought

would move the distribution left, and for

it would be squeezed up. She had been exposed to the formula (1) and was of course thinking that

would have probability density function

, and that

would have

. When I (hopefully) convinced her otherwise, she was concerned that the area under the graph for

would no longer be 1. This is an example of where the student who knows more is more likely to be confused.

In case you are also confused, the general principle is that if has probability density function

, then

has p.d.f.

, and

has

, assuming

. I’ve only ever taught this once, to some fourth year engineering students who needed to know some reliability theory. Should we teach this in Year 12? Should we even mention the formula (1)?

Switching to romantic mode …

It seems that Gauss had an unerring nose for the profound. When two Gaussian functions convolve, their offspring is … another Gaussian. Other L2 functions, those that are not Gaussian, seem to aspire to this; when they convolve their children are smoother and closer to Gaussian in shape. The Fourier spectrum of a Gaussian is a Gaussian. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is the physical equivalent of a mathematical inequality where the extreme case is a Gaussian. Less surprising is that, in Young’s convolution inequality, the critical case is for Gaussians, and this solves a problem relating to Bonsall’s generalization of Hilbert’s famous inequality. All of this relates somehow to the unsolved mystery of the operator norm of the Laplace transform. Perhaps a taste of Gauss’s formula is warranted in secondary schools. Maybe just .

Leave a reply to Mystery Person Cancel reply